|

Restorative Justice: what is it?

Current Western legal systems see crime as breaking the law, and justice as upholding the law by administering punishment, as in the case described above. The needs of all the people involved - the victim, the community and the offender are marginalised. In this way, as well as in its daily functioning, the criminal justice system is often profoundly disrespectful of most of the people involved in it. However, in traditional societies and historically in the West, crime is fundamentally about disrespect, and about harming relationships and community. Justice, in response, is about re- establishing that respect and upholding human dignity. A framework is developing globally for restorative justice practice that borrows from various indigenous cultures around the world who are now reviving ancient social justice practices and customary law.

The framework of restorative justice merges with the mainstream of traditional African conflict resolution practices. These commonalties can be summarized as:

- Both have the objectives of reconciliation and restoring peace and harmony in the community,

- Both seek to restore human dignity,

- Both promote a normative system that stresses an individual's duties, not just rights,

- Both consider all offences as human and personal wrongs against another person(s) and the community at large,

- Both employ procedures that are simple and informal, yet powerful such as carefully prepared and facilitated meetings between victims and offenders

- Both encourage community participation and ownership of the process, therefore those who have offended are more likely to accept responsibility, apologize and offer reparations/restitution for their offense, and

- Both make use of integrative shaming and rituals of cleansing and termination in order to bring about change and healing in the wrongdoer and their victim, in order to incorporate them back into the community as functional members.

The Child Justice Bill is based firmly on the principles of restorative justice. These can be seen very clearly in the chapters on diversion and on sentencing. For more detail, including international documents about restorative justice, please view 'Just RJ" on the Restorative Justice Centre website.

What Restorative Justice is in practice: a case vignette

|

|

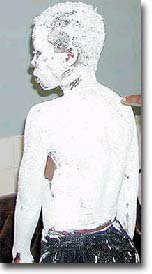

The picture that appeared in The Star newspaper of 'Thandi'

|

Thandi (not her real name), a 14 year old girl, was suspected of shoplifting in a rural town in South Africa. The manager of the shop engaged a workman nearby to paint the upper half of her body, then let her go. As she was leaving the shop one of the security guards took her to the police charge office across the road.

The case went to court. Several months later, the manager was found not guilty and the workman was sentenced to a fine of R 1000. After the magistrate had pronounced sentence, Thandi's family continued sitting in the court, waiting for more. The interpreter told them it was all over and that they could leave.

Speaking to a researcher later, Thandi's mother commented, "how could they paint my daughter - she is not a wall? No one even apologized".

What can we learn from this?

This sketch highlights well some of the shortcomings of our present legal system, not only in South Africa, but across the world:

- As a child suspected of a crime, Thandi was not afforded the usual protections that adult offenders are given - she was presumed guilty and punished immediately;

- Even though the system worked in the sense that it found someone guilty for the wrong done to Thandi and imposed a sentence, this had very little meaning for Thandi, her family and her immediate community. The payment of the fine to the state certainly did nothing to repair the discomfort and loss of dignity she had suffered.

- It is doubtful whether the court process helped the perpetrators, both the one that was found guilty and the one that was not, to understand the meaning of what they had done, to encourage any sense of remorse or repair the harm they had done in any way.

- Presuming that Thandi did take some article from the shop, what she needed was to be shown that this is wrong, and what the consequences for the shopowner and wider community were. The best people to do this would have been her community - her parents, extended family and village. If the system had thought it worth including them in this matter, it would probably have found that they were more than willing to pay for the articles that had been taken, and to ensure that Thandi was disciplined in a firm, constructive and encouraging way.

|

" Latest Version of Bill [B49 of 2002]

" The Bill [B49-2002]

in PDF format

" Fact Sheets on Bill

"Departmental Briefings

" Recosting Report

Search for specific documents on the website

An annotated bibliography collating documents used to inform the process of child justice reform in South Africa

For questions on the Child Justice Act or related topics email

Join the Child Justice Alliance Join the Child Justice Alliance

|